I came to Promising Young Woman a little late—after it won an Oscar, long after most of The Discourse around the film had already died off. About ten minutes in I knew I loved it, and hoped it could sustain its chaotic energy. An hour in, it was my favorite movie of the year. And about fifteen minutes after that, when I’d gotten more coffee and embarked on an immediate second viewing, I figured out why: this is the superhero movie I’ve always wanted, but never thought I’d get.

Let me begin by saying that I’m going to be talking about this film in-depth, so there will be many, many spoilers! Also, consider this a general content warning—this movie is about assault and violence, and we’ll be talking about that, so tread carefully if you need. And finally: I’m putting Promising Young Woman in conversation with Batman, Batman Returns, Batman Begins, The Dark Knight, Spider-Man as a concept, Daredevil’s first season on Netflix, Colossal, Super, and Birds of Prey.

Cassie Thomas and Nina Fisher were best friends who both wanted to be doctors. They got into the same med school, where Cassie soon became the star of her cohort. After a fellow student, Al Monroe, raped Nina at a party (as other students looked on and laughed), Nina was systematically silenced, victim-blamed, slut-shamed, and finally humiliated in court. She dropped out of school, and committed suicide despite Cassie’s efforts to care for her. Cassie, too, left school.

A decade later, Cassie has a “daytime” life of working at a coffeshop and living at in her old bedroom, at home with her increasingly-worried parents. But in her other life, Cassie stalks the night as a vigilante, feigning blackout drunkenness until men take her home with the intent of doing various non-consensual things. Cassie then “sobers up”, and shames them. She doesn’t enact physical punishment—at least, not at first. This behavior has become an addiction for Cassie, in much the same way being Batman is an addiction for Matt Reeves’ take on Bruce Wayne, and it’s framed as such. One day an old classmate-turned-pediatric-surgeon, Ryan Cooper, comes into the coffee shop where Cassie works, and asks her out on a date. She reluctantly goes out with him, and soon her vigilante life and new relationship begin to clash; when she learns he’s still friends with Nina’s attacker she ramps up her attempt at justice. She punishes former classmate Madison McPhee; Elizabeth Walker, the Dean who silenced Nina to protect Al Monroe’s future; and, initially, Monroe’s lawyer, Jordan Green. Finding the man filled with remorse for his actions she forgives him on Nina’s behalf. Madison, in her own attempt at penance, shares a recording of the assault, which is how Cassie learns that Ryan was present and did nothing to help. She blackmails him to get information on Monroe, attempts to violently avenge Nina, and is herself murdered by Monroe. The only reason Monroe faces legal consequences is Jordan Green’s decision to act on the evidence Cassie sent him before her death. The film’s bleak message seems to be that a tiny sliver of justice was only achieved after multiple deaths, the intervention of a high-status man, and the involvement of police—and this has proved understandably problematic for many viewers. It also sets the film up to be a fascinating commentary on the superhero genre.

As in Burton’s Batman, the first episode of Daredevil, Man of Steel, and a number of other superhero films, we’re dropped into Promising Young Woman in media res, meeting Cassie as she’s on patrol in a bar, dressed in business casual, falling out of her seat as she drunkenly looks for her phone. We don’t know what her powers are yet, or what she does to the men who pick her up. When a bro takes her home with him, we stay in the scene just until she reveals that she’s sober… a few seconds after he’s tossed her onto his bed and pulled her underwear off without her consent. We see his shocked face, and then we cut to the next morning as Cassie walks home, smeared in ketchup and eating a hot dog through a smirk. Has she killed him? She goes home, pulls a notebook out of the slats of her bedframe, leaves a hashmark. It isn’t until fifteen minutes into the film that Fennell shows us Cassie’s full routine.

We already know that Cassie uses makeup and wigs to hide her identity, and now we watch her study a YouTube makeup tutorial, create a specific Face, and then smudge that Face to mimic drunkenness. We cut to the scene in a strange apartment, where we see that Cassie’s carefully curated “blowjob lips” are further smudged and faded, having been presumably kissed off by Neil, the man who’s brought her home.

At first it seems like maybe he’s not so bad. (Sure, he’s recommending Consider the Lobster, and talking wayyy too much about his Bright Lights, Big City-esque novel-in-progress—but I’ve done both of those things… shit. Am I a Nice Guy?) Maybe he’s just a lonely, coked-up dude who wants to talk about books? But no: he ignores her when she says she needs to go home, instead rubbing coke on her gums and sticking his hand up her skirt.

Now we see what Cassie does to the men she snares. She asks her “date” if he knows her hobbies, her job, even her name? She points out that he never got consent, and if she hadn’t stopped him just now, that thing he was doing? Was rape. She waits until the horror of his behavior lights up in his eyes. And then… she leaves. She goes home, adds his name and a hashmark to the notebook, and tucks it back under her mattress, and…

And that’s it.

The “punishment” she’s doling out is not physical pain, or public humiliation. She’s not dumping men on the steps of a police station with “Rapist” pinned to their shirts. She’s not even outing them on social media. Cassie’s aim is pure self-knowledge. She’s trying to make her city safer for vulnerable people, one Blurred Lines-enthusiast at a time.

When Promising Young Woman opens, Cassie’s patrolling to bag small game. She believes that Al Monroe, the man whose violence changed the course of Nina’s life and her own, is beyond her reach in Europe. But when Ryan Cooper walks into her coffee shop and recognizes her, he diverts the course of her life once again. After they start dating he mentions being in touch with most of their med school class—including Al Monroe. Monroe’s back in the States and has a job in a hospital. He’s engaged to be married. Ryan isn’t close with him, but he is planning to go to the wedding.

Having established the patterns of Cassie’s life, Fennell now traps her in the same kind of emotional tangle that faces Peter Parker when he finds out his date’s dad is The Vulture in Spider-Man: Homecoming… or Peter Parker, when he realizes his nemesis is his best friend’s dad… or Peter Parker, when he finds out Aunt May is marrying Doc Ock. Should Cassie bury her traumatic past, move on from Nina’s death, and build a future with Ryan? Or use his connections to her old classmates to finally confront her personal supervillain, the man who raped Nina? Cassie tries to balance the life she wants with her Mission—and it goes about as well for her as it usually does for Spider-Man. But we’ll come back to that.

Promising Young Woman was marketed as a revenge thriller, and as much as it’s a twist on rape revenge movies like Death Wish or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, it follows the structure and logic of a superhero movie even more. Cassie constructs a meticulous double life, playing a ‘90’s-style slacker by day, so she can dedicate her “real” life to her Mission—patrolling the clubs and bars of her city for evildoers. Where revenge movies usually focus on a few specific people (think the Bride’s list in Kill Bill), Cassie confronts rape culture as a whole.

And just as Peter Parker, Matt Murdock, Bruce Wayne, and even Clark Kent sometimes trash their super-suits and capes to throw themselves into “normal” life, Cassie has to choose between her Mission and her personal life. And where rape revenge films often revolve around cathartic violence, building a story that allows the audience to root for retribution, Cassie’s purpose has far more in common with the rigid morality of Daredevil or Batman—a yearning for justice. Ground-level, dangerous work to make her city safer for the vulnerable. Dedication to making the world better through vigilantism. But I think even more than that: Cassie’s ultimate goal—even above justice—is forgiveness and healing.

Superheroes and the Feminine Aesthetic

Much was made of the movie’s bubblegum aesthetic when it was released, but what struck me was how Fennell makes stylistic choices that are typical to superhero movies rather than revenge thrillers. It’s always interesting to look at how a filmmaker tells their story through visuals—looking at them through a certain lens also shows how prioritizing one aesthetic explicitly over another can subtly underline whose story is most important. It can even encourage an audience to value one story at another’s expense.

When Batman came out in 1989, it was lauded for “taking comics seriously” and for its gothy, brooding aesthetic. Gotham was transformed into a German Expressionist nightmare, retro 1940’s-style fashion and decor were mashed up with the then-current ‘80s aesthetic, and Burton gave Bruce Wayne and his alter ego plenty of deep shadows to lurk in. As over-the-top as it was, the emphasis on grieving, emotionally complex Bruce also gave his Batman gravity when contrasted with the gleeful anarchy of Jack Nicholson’s Joker. The Joker’s aesthetic was pure comic book: purple suit, face bleached greasepaint white, Day-Glo green hair. And Vicki Vale, for all that she’s a serious photojournalist, is presented as hyperfeminine—and the film makes it clear that her femininity is not an asset in this world. Rather, she becomes an object to be fought over and rescued, and her role as the damsel/love interest is pointed out repeatedly. As Batman, Bruce fat-shames her at one point, asking for her weight as they rappel away from danger and then smirking at her when he decides she’s heavier than she said; as Bruce Wayne, he ghosts her after sex, and when she confronts him he responds by shoving her down into a chair and saying, verbatim: “You’re a nice girl, and I like you a lot, but for right now, shut up”—because her hurt and confusion pale in comparison to his need to tell her he dresses as a bat to beat up criminals.

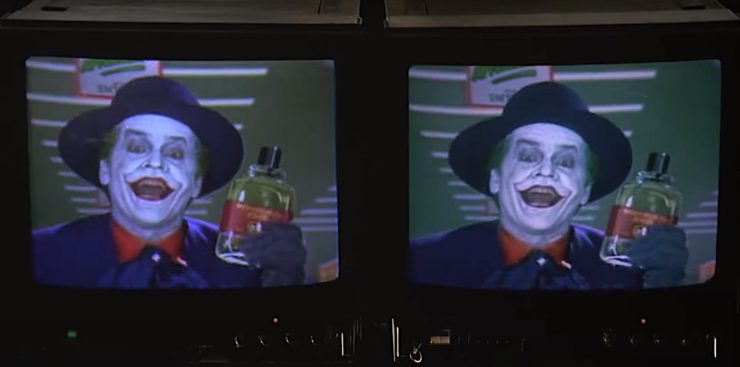

And what of the film’s plot? The Joker’s first true supervillain outing comes when he tampers with beauty products—a man whose own face and hair have been permanently altered to look made-up literally makes beauty toxic. The film presents this mass poisoning as a darkly comic running gag. First, we watch a female newscaster laugh herself to death on air, as her male co-anchor is reporting on inexplicable deaths at a beauty salon, and the joke continues as the male anchor and his (new) female co-anchor host the news in increasingly disheveled states, with frizzy hair, sallow skin, and zits on full display. It’s a clever way to show the crisis, and it shows how the toxic products are affecting Gotham across gender lines. Of course this doesn’t affect the headliners: when Batman takes Vicki back to the Batcave to give her his breakdown of the Joker’s plot, we get to watch a superhero (wearing eyeliner) tell a woman (wearing visible lipstick, eyeliner, mascara, and big-ass ‘80s hair) that “Hairspray, mixed with lipstick and perfume, will be toxic and untraceable” so she can report it the next day and warn Gotham.

So to sum up: the frivolity of make-up is mocked (but our leads still look gorgeous) and the anarchy of the Joker is vilified, and there’s a subtext of women being vain and lying about their weight, serving as the object of sexual competition and nothing else, and, of course, the perennial accusation of being overemotional, and in the end the day is saved by the Dark Angry Goth Who Wears Sensible Suits By Day.

This anti-feminine subtext is complicated, but I think ultimately reinforced, in Batman Returns. When we meet Selina Kyle she’s a mousy, frazzled, quivering woman in a drab brown skirt suit, hunching over to make herself small, half-heartedly trying to speak up in a boardroom full of men who want her to keep her mouth shut and pour coffee. Selina is introduced as an archetype of the failed Career Girl: a woman who moved to the Big City to pursue her dreams, but ended up in a thankless job, at the beck and call of men who don’t respect her and will never see her as an equal—hell, they’ll never really see her at all.

And then she takes us home.

I’ve talked about Selina’s apartment before, but to sum up: it’s a riot of pink, floral curtains, yellow squashy chairs, the buzzing pink neon sign singing “Hello There”—her home shows us that Selina doesn’t just have a personality tucked away under her office demeanor, but a vibrant personality that embraces color and a certain type of femininity. But again, as in Batman—after Shreck murders her and the cats bring her back to life, she sprays black paint over her pink walls, destroys a cute sweatshirt with kittens on it, sweeps her work clothes and t-shirts aside to find the latex for her catsuit. From then on when we see her she’s either Catwoman, or she’s dressed in sleek blacks, whites, and greys, just like Bruce, Shreck, and the Penguin. The only way for her to be on equal footing with the male heroes and villains is to trade her pinks and yellows for their darker, serious tones.

During her initial “patrols” Cassie employs a variety of costumes. The ones we see are: Business Casual Woman in a Pencil Skirt (too many drinks after work, bait for finance bros and lawyers); Pigtailed Girl (blurs the lines of the age of consent, bait for… I don’t want to think about it); Hipster Cool Girl in a leopard midi (bait for Hipster Guy Neil, who wants to tell you all about his novel); Bodycon (bait for the kind of guy who would wear a fedora). But part of the fun of the movie, and why I think it works so well as a superhero riff, is that Cassie really does look like a different person in each of her costumes. She takes her double life so seriously, and has dedicated herself to it so obsessively, that when she patrols she becomes the archetypes she’s playing.

And it isn’t just Cassie. Fennell makes sure to give each character a real-world take on a superhero costume. When Ryan talks about their old friend Madison, he mentions that she’s “obsessed” with her newborn twins, but when we meet her, it’s in a form-fitting white sundress, bright red lipstick, and long-ish, styled hair. Speaking as a former full-time childcare worker, her look screams: “I have the money for a housekeeper and at least a part-time nanny.” Her costume—and it’s absolutely a costume—is meant to show that she’s been able to maintain her looks and her class status in the face of a pair of babies. Amber Walker is cosplaying Cher Horowitz from Clueless, and her mom, the Dean of Forrest Medical School who covered up Nina’s rape allegations, is dressed in a dark brown power suit—the sleeker version of Selina’s dowdy work outfit, actually. The various bros and Nice Guys are usually in some variation on business casual, with the occasional suit or trilby, and Hipster Nice Guy wears blue plaid. Which leads us into what I think is Fennell’s best choice: Ryan Cooper is almost always in blue. Not to the extent that it seems cartoonish, but he’s nearly always in a blue button-down, blue plaid, blue sweater. He wears blue scrubs—his superhero cape! The last time we see him, it’s in a pale blue suit at Al Monroe’s wedding.

You know who else always wears a signature color? The Purple Man. And Joker. And Penguin. And Max Shreck. And Wilson Fisk. What Fennell has been subtly doing throughout is telling us a different truth: despite what Cassie believes, Al Monroe is not her supervillain. He might be Nina’s, but she’s no longer here to fight him. Cassie’s supervillain is Ryan. Cassie’s the one who has waged a war on Nice Guys, and Ryan is the Final Boss of Nice Guys.

Ryan’s baby boy blue provides a perfect contrast with Cassie’s tendency toward pinks and florals. Especially in the pharmacy scene, her bright pink top and pink jeans pop perfectly against his blue shirt, the pink neon sign buzzing above them. It’s gorgeous—but also realistic. And as she falls further into his orbit, we watch as her clothing choices change. Before she was only in blue once, for the pieta-esque scene in which she forgive lawyer Jordan Green, and in that scene it is pretty clearly a riff on traditional depictions of Mary.

But the more time she spends with Ryan, the more often she’s in blue, until, in the scene when he tells her he’s falling in love with her, the blue pajamas she’s wearing (his, maybe?) match his blue sheets so exactly she’s literally disappearing into them. She’s in blue when she learns the truth about him, and when she confronts him with that truth—and then, the next time we see her, the last time we see her, it’s in her stark white-and-red Sexy Nurse Costume.

Lairs!

In Burton’s Batman, the Batcave is a tech-heavy lair under the house, accessible via a secret iron maiden elevator. In Nolan’s take, it’s a literal cave full of bats—the Waynes used to use it as a stop on the Underground Railroad for maximum moral underscoring. Now, Vicki Vale’s lair? Her chic and mid-80s modern apartment is devoid of personality…except for her extremely femme bed, which we’ll talk a bit more about below. In contrast to Vicki’s apartment, Selina’s one-bedroom is, as I mentioned, an explosion of pink. (I’ve painted a lot of apartments over the years, and getting every centimeter of that apartment that shade of pink was a serious investment of time.) I’m going to assume that, just as she sews her own catsuit, she re-upholstered her furniture and made all the cute little tea rose patterned curtains. You can imagine her creating this home, bit by bit—an oasis in the middle of an uncaring city. Selina’s lair is one aspect of her personality—the part that she loses when Max Shreck murders her.

Cassie is also stuck in a state of arrested development. Her lair is her childhood bedroom: pink, frothy, baroque, covered in pictures of Nina. Unlike Batman, who often operates from behind a bank of computer screens, Cassie—quite appropriately both for her mission and her status as a Millennial—operates her sexual vigilantism primarily from bed. She keeps her notebook tucked under her bedframe, a perfect fusion of Matt Murdock’s Hidden Chest of Daredevil Stuff and a pubescent girl’s Secret Diary.

She sits in bed while she researches her Supervillain’s bachelor party on her laptop. In a mirror of Selina Kyle, she only leaves the bed to work at her vanity, where she can watch makeup tutorials to create each night’s disguise before going on patrol. When she’s dating Ryan we only see her at his apartment (like Vicki’s, it is a blank, spare, simulacra of a living space) and presumably he never spends the night at hers, as it would be awkward as a thirty-year-old woman who to bring a boyfriend back to the home she shares with her parents.

And what of Ryan’s lair? Well, his, as I mentioned, is not his soulless apartment—it’s his office at the hospital. We only see it twice, once when Cassie confronts him with his own moral failing, and once when, questioned about Cassie’s disappearance, he chooses to lie rather than tell the police what he knows. Once again blue is the dominant color, but the personality comes through in the crayon drawings of his grateful patients. Rather than keeping them in a file as personal gifts from patients, he displays them. They become external proof that he is A Good Person, trophies of his successes as a doctor. The career that neither Cassie nor Nina were able to pursue.

The aesthetic of Promising Young Woman is so strong that it became an overwhelming part of discussion of the film. What is the story we’re being told? In Batman and Batman Returns, it’s that the stereotypically feminine aesthetic has to be subsumed by the darker masculine one. This is reinforced by every frame of Nolan’s Batman movies, but every frame of Zack Snyder’s work with the DCU, and by much of the drab, dishwatery Marvel aesthetic (with all due allowances made for Thor: Ragnarok and the Guardians movies). It’s only in Wonder Woman and, more so, Birds of Prey, that brighter, poppier colors are allowed to “win.” Cassie only briefly allows her aesthetic to be swallowed—specifically during her interlude with Ryan. She confronts him in “his” color, and then reverts back to fully to her own aesthetic: When she faces Al Monroe it’s in a multicolored wig and her signature manicure, bright pink bubblegum popping in her mouth.

Sexual Violence and Superheroics

Because Promising Young Woman is a film that deals with dark themes of sexual assault and consent, and especially given how often superhero movies use rape, or implied rape, as a plot point, I’m going to have to talk about it for a few paragraphs. Skip down three paragraphs if you need to—you can rejoin the article at the Double Lives/Double Standards subheading.

Both the 2003 Daredevil and Netflix’s Daredevil take time to show us Matt Murdock specifically punishing rapists, and rescuing women and children from traffickers. Jessica Jones’ entire first season revolved around issues of consent, rape, and trauma as she battled The Purple Man. While most of the violence in Birds of Prey leans cartoonish, the thing that brings Harley Quinn and Dinah Lance together is Dinah saving an inebriated Harley from a very real, very-not-cartoonish threat of rape. But the two most complicated instances come in Batman Returns and Spider-Man.

In Batman Returns, Selina Kyle’s first time out as Catwoman is not a canonical callback jewelry heist, or anything to do with her main antagonist Max Shreck—instead she intervenes when a woman is dragged into an alley by an attempted rapist.

When the woman attempts to thank Catwoman, in a mirror of Selina thanking Batman at the opening of the film, the normally meek Selina lashes out at the woman she’s saved, telling her “You make it so easy for them!” with exactly the victim-blaming mentality and internalized misogyny that Cassie fights in Promising Young Woman.

In Raimi’s Spider-Man, a group of men follow Mary Jane into, say it with me now, a dark alley. This moment is even more jarring than the similar scene in Batman Returns, because in the midst of this fairly PG-13 film, gang rape is suddenly a very real danger. Of course Spider-Man gets there in time, and we spend long moments watching Spider-Man hit the attackers until they don’t get up anymore. We get the cathartic thrill of watching a superhero dole out punishment.

But here again, things get weird after the rescue. Because the horror of seeing Mary Jane nearly gang-raped is utterly subsumed in the iconic upside-down kiss she shares with Spidey mere seconds later.

And yeah, I was all in on that kiss the first time I saw it, but it’s kind of troubling to me in retrospect—how did we all accept that? That a moment of violence and terror could be redirected into a consensual make-out session with a masked stranger? As the guys who followed her into the alley with ill intent lie a few feet away, twitching and unconscious? Wasn’t that a little… off-putting?

Promising Young Woman unpacks a lot of the overt and covert sexual violence of superhero media. In a brilliant bit of nuance, Fennell never has the word “rape” appear the film. Everyone talks around it, as though it would be impolite to name the thing that was done to Cassie’s best friend. Cassie punishes this specifically by going after her old friend Madison. Cassies invites her to lunch, allows the other woman to get drunk, and then turns her over to man she’s hired to leave Madison in a hotel room. Now, the man doesn’t do anything to Madison. Cassie’s just creates a horrific scenario in which Madison wakes up in a strange room, with a strange man, and can’t remember what happened. Now I want to be clear that this is horrifying. But. Cassie didn’t ply Madison with drinks. She didn’t roofie her. She simply created a situation where Madison could let her guard down, and, rather than stepping in to protect her, left her (seemingly) vulnerable. Except of course, Madison wasn’t ever vulnerable. Not really. Not like Nina was on the night of the attack, when Madison failed to protect her, and then covered her own guilt by slut-shaming her.

On the one hand, Cassie pushes back against the mindset that made Selina sneer at a woman after saving her; on the other, her punishment of Madison, which arguably goes too far, also leads directly to her learning the truth about Ryan. In this moment she destroys any hope she had of starting the happy new life that her family, friends, and even Nina’s mother so desperately want for her; she also frees herself from the lie that Ryan has trapped her in. They’re inextricable.

Fennell doesn’t show rape… or at least, not the sort of Game of Thrones, Girl with the Dragon Tattoo type scenario. We see two men put their hands in places they should not be putting their hands without clear, enthusiastic consent—and in both cases that’s the trigger for Cassie to reveal her sobriety and shift into Avenging Angel mode. We never see what was done to Nina—Cassie watches the video, and we can tell from her horrified reaction that this was not, by any measure, consensual, or a misunderstanding. If we strain we can hear Nina, but her voice is drowned out by the howling men around her, and then, of course, by Ryan’s uproarious laughter.

But we never see them, because they are not, and should not be, the focus of this scene. What we see is the consequence of Al Monroe’s action, and Ryan’s inaction. We watch Cassie’s heart break. Seeing her reaction, and the inconsolable grief that follows, sends us into Cassie’s final confrontations with Ryan and Al Monroe in a very different frame of mind. We don’t necessarily want to see them tortured—we want to see Cassie healed. We want justice, not revenge.

Double Lives/Double Standards

A superhero is allowed to be obsessive, dark, dual-lived—at least, a male superhero is. Female superheroes are still subject to a madonna/whore complex. The DCEU’s version of Diana Prince is, frankly, perfect—sweet, wholesome, brave, loving, witty, unshakeable. In Captain Marvel, Carol Danvers is brave and snarky, fighting her way back from various types of abuse and gaslighting, risking her own life for her mentor, giving up any of her future plans to fly around the solar system righting wrongs. Her personal life seems to extend to being a chaste partner to Maria Rambeau, and an aunt to Maria’s daughter Monica, and while plenty of people theorize about her sexuality because of that haircut, she has neither confirmed nor denied her romantic interests. Natasha Romanov, spy-turned-superhero, is expected to use her sexuality and feminine wiles in the service of the government. In the MCU she’s introduced as a former underwear model, and thus endlessly objectified by Tony before her true identity is revealed, and later, of course, there’s the whole Red Room/sterilization plotline in Age of Ultron. Elektra is tangled in endless psychosexual rehash cycle with Matt Murdock. Harley Quinn isn’t exactly a hero, is tied inextricably to the Joker, and is, again, objectified by all the men in her standalone movie. Catwoman and Poison Ivy are often defined as the sexy alter egos of the mousier Selina Kyle and bespectacled Pamela Isley. And one of Batgirl’s last big outings featured a truly nonsensical sex scene with Batman that I’m still not even remotely over. (And granted, all of these characters are more nuanced in the books, but the film versions? Usually aren’t given the same room for nuance that their male counterparts are.)

Now, to be clear: I am (Very! Extremely!) pro-underwear modeling, pro-sex work, and, for that matter, pro-sex. However! Tony Stark doesn’t have a Calvin Klein ad campaign in his backstory for Natasha to tease him about, and he’s also allowed to be “complex” and “troubled” and sleep with Christine Everhart—but it’s Christine, the serious journalist who chooses to go to bed with a charming man, who gets called “trash.” By Pepper, no less. Batman, with all of his violent, obsessive behavior, is taken seriously in a way that Catwoman and Poison Ivy are not—despite the fact that in some iterations of their stories Selina is a feminist hero, and Ivy is, always, exactly the eco-warrior the Earth needs.

This gap is threaded through in every aspect of the subgenre—the aesthetics I mention above, the way male heroes are coded in games versus female heroes, the arguments about whether Batman does that—all of it adds up to the idea that even in a superheroic universe, where all bets of reality are off, women have to toe an absurd moral and aesthetic line in order to be deemed “heroic.”

Fennell shows us that Cassie is dark and complicated. She often does things that are cruel. She’s obsessive. She visits Nina’s mother—visits that Fennell refers to as “hauntings”—even though the woman urges Cassie to move on. She is spiky and furious. She’s able to live her double life because her upper middle-class parents can afford to let her live at home for free. She can coast through her coffee shop job because her Black female boss loves her and supports her. She can get away with her patrols because she’s pretty, blonde, and white. She’s also incredibly, impossibly loving. She visits Nina’s mom because, like any good superhero, she’s wracked with guilt. (If Peter had stopped that thief, Uncle Ben would still be alive; if Nolan’s version of Bruce had been a little braver, Thomas and Martha Wayne would still be alive; if Cassie had just gone to that party, Nina would still be alive.) When she falls for Ryan, she brings him home for dinner because she wants her parents to like him. She brings him to the coffee shop because she wants Gail to approve of him. She wants to be happy, and she wants the people she loves to be proud of her. She can wiggle into a bodycon dress and still be shot like the Pieta when she offer forgiveness rather than vengeance to Al Munroe’s remorseful lawyer, Jordan Green. She can make Ryan drink her spit and still be framed like an icon of Mary.

And speaking of spit…

Sexuality, Superheroes, Superfreaks, and The Coffee Scene.

Recent superhero movies have tended to come in two flavors: bright, PG-rated, Disney-fied adventure stories that are appropriate for the whole family, and dour, bombastic, EPIC MYTHS. (Not to oversimplify, but I think of it as movies that are following the lead of Richard Donner’s Superman versus those who are walking the path of Nolan.) But when superheroes first conquered the movies between 1989 and 2002, that’s not how the subgenre was at all. The Batman movies went from Goth and weird (Burton!) to queer and weird (Schumacher!), the X-Men movies were full of coming out allegories and love triangles, and Raimi’s Spider-Man was cheesy (in a good way) but also tortured and angsty as hell. Part of the point of the superheroic subgenre was to wrestle with weird pathologies, obsessions, double lives—and the kind of psychosexual drama that can only be expressed through layers of latex and roleplay.

But this is a nebulous topic? So let me give you concrete examples. Batman has a whisper of a subplot, never fully developed, in which Vicki Vale comes to Gotham because, and I’m quoting her here, “I like…bats.” She wasn’t there because of mob violence, or even rumors of costumed vigilantism—it’s heavily implied that she’s turned on by bats. She is attracted to the idea of a guy who dresses as a bat. And the few times she interacts with Bruce-Wayne-as-Batman we see the hints of a very different movie, with a very, um, specific agenda. But unfortunately the “Vicki Vale: Freak for Bats” idea isn’t developed fully, instead being subsumed into a far more disturbing scene that we’ll discuss in a few paragraphs.

Immediately after Batman became The Biggest Movie Ever there was a unique cultural moment when Tim Burton could do pretty much anything he wanted. And what he wanted was to put fetish outfits into PG-13 movies. This wasn’t David Cronenberg operating on the fringes of Canadian indie cinema, or queer af Clive Barker making horror films that took bondage hoods in one hand and William Blake’s art in the other and said “…now kiss”. This was Burton creating a modern fairy tale in Edward Scissorhands, and selling tween girls Johnny Depp in head-to-toe bondage gear. This was him taking the idea of a “catsuit” and turning it into shiny, skintight, stitched together latex, and giving America a complex superhero story starring a feminist antiheroine who beats up her boyfriend and wields a bullwhip.

This was, uhhhhh, weird. Not that any of this stuff is weird on its own! I just mean weird to be included in two giant mainstream movies aimed primarily at high school kids and college-age Mall Goths.

But it also makes perfect sense, in a bone-deep way? Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle are complicated people working through trauma via roleplay and occasional vigilantism—it makes sense that they also use these tools to express their sexuality. It makes sense that Matt Murdock is trapped in a hurt/comfort cycle with Claire and Karen, before falling back into the violent drama of Being In Love With Elektra Even If It Annoys God. It makes sense that MJ is maybe more into Peter in the Spidey suit than out of it. Superheroes-and-villains have these dynamics because the point of them is to live their lives on a mythic scale—so why would their sex lives be any different?

This all makes sense? OK, cool, now we’re going to talk about violence and SPIT.

During Selina and Bruce’s one attempt at a date, she pounces on him and they make out for a second, but then they both rethink it and back away from each other.

The reason for backing off? They’re both still reeling from flirt-fighting as Batman and Catwoman, a skirmish that culminated in her stabbing him with a claw. Later, as he removes the claw from his ribs, he gazes at it and licks his lips. Which sets a certain tone that the film follows through on in their next meeting, which, unbeknownst to them is happening only a few hours after their attempt at a date.

Even more than their first fight, this one becomes a struggle over power dynamics. When he ends up on his back with her kneeling on his chest he seems… fine with it, actually. They listen to their latex creaking, and share banter about kisses under the mistletoe. And then she licks his face.

He responds in the only reasonable way by sucking on his lower lip again, and for a second it seems like things are going to go in a very different direction—but then she claws him and he throws her across the roof. In this PG-13 world, where the hero and the anti-heroine can’t just go to bed, they sublimate their obvious attraction into exchanging spit in unconventional ways, and almost killing each other. And the film expects us to believe in this romance enough that at the end of the film we’ll hope that Selina gives up her Mission to go home with Bruce. (And I do, goddammit. Every stupid Christmas.) For all the many flaws of Netflix’s Defenders, one thing that worked beautifully was the idea that Matt would stay with Elektra as a building crashed down around them—their love is too big and too fucked up to be contained by Date Nights and Wedding Registries, and has to be sublimated into a giant, symbolic death. For all the many flaws of Spider-Man 3, one aspect I loved was that in the end it came down to Peter and MJ still trying to work their shit out via symbolism.

The mostly realistic world of Promising Young Woman only has so much room for sublimation and symbolism. Cassie’s a regular, small, non-superpowered woman, and the kind of men she’s dealing with are exactly the kind who kill the possibility of the sexually-charged fighting that come as a second nature to Batman and Catwoman, or Daredevil and Elektra. When there is violence during Cassie’s patrols it’s purely dangerous; the one time we see one of her attempts at “judgment” go wrong, in fact, it proves fatal.

What Cassie’s life does allow for, however, is spit.

When Ryan walks into the coffee shop, he doesn’t greet Cassie, or acknowledge that she’s reading. He doesn’t see her as a person, because, just like Selina Kyle in that conference room, she’s a woman in a service position, a cog in the clock of his day. He wants her to hand his coffee over with minimal personal contact. It’s not until he recognizes her as a former classmate that he makes eye contact with her and says her name. He instantaneously fucks up a potential meet cute by asking why she’s working in a coffee shop—he’s shocked that someone he went to school with could be working-class, and clearly thinks that, according to his mental power dynamic, she should offer up an explanation when it’s demanded of her.

But in trying to apologize for his gaffe, the movie veers in a direction that opens up a whole world of subtext. Ryan tells Cassie that she can spit in his coffee as revenge for his rudeness. Cassie, with no hesitation, spits. (And it’s not some cute little cartoonish ‘ptooey’ of spit, it’s a lump that takes a second to dribble into the coffee. It’s gross.)

THEN he asks her out, staring at the floor. When she hesitates, he re-establishes eye contact and drinks the spit coffee. Like, almost all of it. While staring her down.

Again, weird! Not on its own, but in the context of this film, this moment is an odd spike of power dynamics and flirtation—the closest this movie can come, in fact, to flirt-fighting. Fennell underscores the power negotiation by playing with eyelines—Cassie seems to be looking down in amusement while Ryan gazes up at her as he drinks, which given their height difference is impossible, but it’s a beautiful way to show that Cassie is the one in control at this moment. She remains in control, in fact, until the moment her dual lives intersect in the club parking lot.

Normal Life vs The Mission

When the film begins there are small hints that cracks are starting to show in Cassie’s facade. Gail mentions that a mutual friend saw her at a club; Mr. and Mrs. Thomas are so fed up with their boomeranged daughter that they give her a suitcase for her 30th birthday. But it’s Ryan who, in two instances, forces Cassie’s lives together.

After their first date, she spends the next weeks rededicated to the Mission, leaving regular patrols behind to focus on confronting two of the women who were complicit in the assault on Nina. She holds mirrors up to Madison and Dean Elizabeth Walker, showing them that they are both operating as tools of a misogynist system. But when Cassie chooses to escalate, she starts a domino effect—just as Matt Murdock and Bruce Wayne set their lives on certain paths in facing off with Fisk and the Joker, Cassie’s decision to go from small acts of local vigilantism to attacking “The Patriarchy” as a concept ends up changing the course of her life. If it wasn’t for Ryan walking into her life, she wouldn’t have the puzzle piece that Al Monroe was back in the States. She wouldn’t have the infuriating knowledge that he’s madly in love, about to get married, has a career: everything Cassie wanted for Nina, and for herself.

Ryan bumps into her on patrol, when she’s going home with Nice Guy In A Trilby. He recognizes her, and for the first time her worlds collide. She stammers out some excuses, he’s wounded. This leads to her ending the patrol, but first, Trilby Man says that he’s heard about her. For the first time we get a hint that there’s a Batman-esque rumor circulating among the “Nice Guys” of The City, a whisper network, if you will, of bros warning each other about the gorgeous blonde who pretends to be drunk. Cassie decides to thread a needle at this point, building on the rumor by claiming that there’s another woman out there who actually uses violence. Whether the woman is real or not doesn’t matter in this moment—what matters is that Cassie is upping the stakes, and foreshadowing her own later path. What matters is that her attempts to be normal and date a cute boy have crashed headlong into her Mission. And this collision is what seals her fate.

She apologizes to Ryan, but doesn’t explain what she’s doing, or why. This is not “Bruce and Selina tear their masks off and get real” or “Matt and Foggy talk through Matt’s double life and Foggy gradually forgives him and comes around over a few months, Nelson & Murdock 5eva.” She promises that “it won’t happen again”, but when he brings up the fact that she won’t kiss him, she panics and flees. Feeling like she’ll never have a normal life, she heads into the confrontation with Al Monroe’s lawyer, Jordan Green. This is where the film reaches a certain kind of climax, because, for the first time on screen, we see a man own up to his behavior and ask Cassie’s forgiveness. And she does forgive him in the softly-lit Pieta scene I mentioned above.

In Fennell’s world, the complicated superhero can be fucked up, but also morally corrects enough to offer meaningful forgiveness. Having finally had the catharsis of forgiving someone rather than judging them, she goes straight to Nina’s mother to try to expiate her own guilt, and Nina’s mom all but demands that she move on with her life.

If the movie ended here it would be uplifting, in a way: a woman became a costumed vigilante, found and lost love, but was finally able to forgive someone, and moved on with her life. Instead, Ryan walks back into the coffee shop—and when he leans in to kiss her it’s very much him asserting his will, and her acquiescing to it. It’s one of the only times Fennell emphasizes the height difference between the actors, with the shot underlining that whatever power Cassie had is gone. He caught her being a “slut” with Trilby Man, has decided to “forgive” her, and now the relationship is going to proceed on his terms.

Cassie’s commitment to Ryan brings her a stark choice. Possibly for the first time in her life she’s genuinely falling in love with someone. She lets her guard down. She throws The Notebook away. She takes one last, long look at the event page for Al Monroe’s bachelor party before deleting her “Freindbook” account. She has a chance at a life with Ryan and real happiness, and she’s going to leave her Mission behind. But as in any superhero movie, things are never so simple. Selina would love to run away to Bruce’s castle “just like in the fairy tale”, but no court will punish Max Shreck for what he’s done, and her own past terrorist acts are too huge to walk away from. Even once Nolan’s Batman captures the Joker, there are still Harvey Dent’s crimes to clean up, which finally lead Batman to take the fall to save Gotham’s soul. Raimi’s trilogy ends on that long, ambiguous shot of Peter and MJ’s hands—but who knows if those two crazy kids work it out? And it took Matt a whole third season to get over Elektra and make up with God. Cassie’s secret life comes back to destroy her mainstream one: when Cassie “punished” Madison, that forced the woman to confront her own role in Nina’s death; in an attempt to come clean, she gives Cassie the first video evidence of what Al did to Nina. And so, after months of bliss, Cassie learns the truth about Ryan.

She walks into the bachelor party in her final form: no longer a drunk girl laying a trap, she’s now The Stripper in a Sexy Nurse Costume. Unlike all of those stalwart heroic men I’ve been talking about, Cassie is a normal person. She has no superpowers, no alien blood, no trust fund, no stately manor. When she chooses to confront her supervillain, the only armor she can give herself are two layers of personae, a more extreme take on her usual makeup, and a wig that matches her manicure. Her weapons are a roofie-laced bottle of vodka to drug the groomsmen, and, presumably, the private joke that she’s confronting them as a fake nurse rather than the doctor she planned to be. Ironically, this is the most she ever looks like the Joker.

Speaking of whom, let’s dip back into Batman for a sec. Right before Batman takes Vicki to the Batcave and gives her the intel on the Joker’s cosmetics poisoning plot, she snaps a couple photos of him. Because, as she’s said repeatedly, she’s only here to research and publish a story on The Batman of Gotham. (And maybe be kind of a freak about the whole bat thing, but that’s strictly after work.) She finally gets her chance. She does her job. And before Batman takes her home, he seems to flirt with her, and tells her, “There is something else you have that I want!” He flings his cape up and we hear the shrieking of bats.

The film cuts to Vicki face-down on that hyperfeminine bed I mentioned earlier. She’s still in the blue dress she was wearing earlier, her skirt hiked up to her ass. Her white tights have lines of dirt up the seams. As she comes awake, her hand flies to her chest, and she moans “Ugh, he took the film!” The phone rings, and it’s her writing partner Knox. Hearing her muffled, hungover voice, he immediately asks if he can come over in his most sex-pesty voice.

To recap: Batman roofied Vicki, rifled around in her bra for the film, took her home unconscious, flung her face-down and sideways across her bed, and left. He didn’t lay her on her back with her head on one of the many pillows. He didn’t put a blanket over her. He didn’t even tug her skirt down. This is, again, a woman he’s slept with. A woman he likes enough to almost divulge his double life. A professional woman, who was doing her job—as opposed to a vigilante taking the law into his own hands.

I mention this scene specifically because Vicki, drugged and disheveled, looks eerily similar to our last sight of Cassie, a vigilante who took the law into her own hands. Having roofied Al Monroe’s groomsmen, she shackles Al to the bed with fuzzy handcuffs as he reassures her that he’s a “gentleman.” She threatens him with a scalpel in a dark parody of the doctor she never got to be, and in response, he breaks free of the play handcuffs and smothers her with a pillow. The last time we see her, she’s in the hiked-up skirt of the Sexy Nurse costume and dirty tights. Utterly disrespected. A body, not a person. An obstacle to be dealt with.

When Cassie revealed the scalpels, part of me wanted that cathartic violence. Part of me wanted to see her carve Nina’s name onto Al’s skin, even knowing that there’s no going back from something like that. Part of me wanted to revel in seeing him terrified and in pain. It’s the same part of me that feels nothing but exhilaration watching all of Joker’s plans come together. Just sheer sick joy at the idea that rules are out the window. But the reason Promising Young Woman is a brilliant film is that my desire for catharsis is, as I said, sick. It’s impossible in this non-superpowered world to avenge what was done to Nina. With no super strength to protect her, Cassie is easily overpowered by Al. As in two other films that blur the lines between realism and “genre”, Colossal and Super—when real, physically weaker people come up against larger or better trained people—anger or righteousness or will is simply not enough to tip the balance. In Colossal, Gloria can drunkenly pilot a kaiju and wallop Seoul, but her would-be boyfriend Oscar can still beat the shit out of her in the film’s reality because he’s twice her size. In Super, Frank Darbo can feel inspired to become the superhero The Crimson Bolt, but he’s not really capable of battling homicidal drug lords. Al Monroe murders Cassie, smothering her long past the point of self-defense. From his perspective, however, he’s protecting himself from a crazy woman, not subverting long-overdue justice.

But before realism’s grip gets a little too strong, Fennell returns us to a more superheroic plot. Just as Bruce Wayne rigs his invasive sonar system to self-destruct to reward Lucius Fox’s trust in him in The Dark Knight, so Cassie has created a back-up plan. She sent the video of the assault to Jordan Green. She prescheduled texts to Ryan, ensuring that she and Nina get the last words in the film.

With no justice, no reconciliation, no path for mourning, it’s impossible for Cassie to return to the life she planned for herself. Nina’s family have to live the rest of their lives without their daughter, now Cassie’s parents will have to do the same. Everyone in Al Monroe’s orbit will be affected. Ryan’s career is likely over, because even if Al isn’t charged, surely someone will leak the video. Surely the group will guess that Madison tipped Cassie off, and surely Dean Walker’s record will be harrowed up.

Some people have blasted the movie for including this slightly fantastical element, either because they see it as too unrealistic, or because they think involving the U.S. justice system is a (literal) cop out. And I get that! But I’m glad Fennell gave me this tiny moment of severely qualified wish fulfillment. The reason I truly love this movie, though, and the reason I wanted to write about it, is where it veers off course for both a superhero movie and a classic revenge thriller. It’s an anti-Avengers movie, an anti-Batman, showing us how justice is, in many ways, impossible. This movie is all about how violence is never the catharsis you want it to be, vengeance is hollow. Promising Young Woman is ultimately a superhero film about forgiveness, not revenge.

Just to be clear, Leah Schnelbach still has more to say about this movie. (They didn’t even get into Birds of Prey.) But they should probably stop now. Come sing “Stars are Blind” with them on Twitter!